In this chapter and the next we consider the main legal danger to journalists: defamation. In this chapter we look at what defamation is and what most defamation laws say you must not do. In the next chapter we consider the various defences which you might be able to use if you are sued for defamation; and we see how defamation is punished.

______________________________________________________

Words are very powerful. Journalists use them to inform, entertain and educate their readers and listeners. Words can be used to expose faults or abuses in society and to identify people who are to blame.

However, used wrongly or unwisely, they can do harm. Words can misinform the public and they can hurt people with false accusations. At one stroke words can destroy a reputation which someone has spent a lifetime building. So people must be protected from the wrongful use of words.

Most countries do this with the help of laws, the most important of which are laws of defamation.

There is no need to fear the laws of defamation if you take the time to understand them and then take care over what you write. Laws of defamation apply to everyone in society and they exist to protect people from abuse. In democratic societies they are not there to stop journalists doing their job.

They should not be a problem if you do your job properly by taking care over how you gather information, how you check that it is true and how you write accurately, sticking to facts.

What is defamation?

Very simply, defamation is to spread bad reports about someone which could do them harm.

Of course, the laws of defamation say more than that, but it is a good place to start. The verb is to defame and the words used are said to be defamatory. You can defame someone if you write or say something about them which spoils their good reputation, which makes people want to avoid them or which hurts them in their work or their profession.

Laws of defamation vary from society to society, even those based on English common law. (For more on common law, see Chapter 63 Introduction to the law.) This is especially so on the issue of truth. In common law, a matter normally has to be false to be defamatory. However, some systems have passed laws (statutes) that truth alone is not a complete defence. And even in common law systems it is the responsibility of the person making the accusation to prove it is true; it is not the responsibility of the victim to prove it is false. This is an important distinction for journalists and we will speak more of it later in this chapter and in the following chapter.

If someone complains to the court that you have defamed them, they are called the plaintiff. Because defamation is usually a civil wrong, when people take court action, they are said to sue for defamation.

Before the mass media became so important, defamation was usually done by word of mouth, often by rumour or gossip. Today, many cases of defamation relate to the media.

To defame someone, journalists do not have to make up false things themselves. You can defame a person by repeating words spoken by someone else, for example an interviewee. It is no defence to claim that you were only quoting someone else. If you write something defamatory, you could be taken to court, along with your editor, your publisher and printer or your broadcasting authority, the person who said the words in the first place ... even the newspaper seller.

As already mentioned, one of the problems with describing how defamation laws can affect you is that they differ from country to country. After reading this chapter and the next, you will need to do some research of your own, by asking local lawyers for advice.

Although all lawyers should know something about defamation, it has become such a specialist area of the law that some lawyers are expert in it, while others are not. Find an expert to ask. Your news organisation may have a special lawyer who advises on matters such as defamation.

Libel and slander

Before we move on, a word about libel and slander. These are words for different kinds of defamation. Years ago, the difference between libel and slander was that libel was the written word, while slander was the spoken word.

With the development of the press, libel became the most widespread form of defamation. When broadcasting was introduced, most legal systems decided to treat radio and television like the press and apply the laws of libel to them, even though their words are spoken. For the purposes of these chapters, we will use only the single term defamation.

^^back to the top

A definition of defamation

Your country may have laws protecting freedom of speech and publication. These may be part of your Constitution. There will probably also be laws of defamation to protect people from false accusations. In most Commonwealth countries, the defamation laws are based on English law. Those countries which gained independence after World War II usually follow the rules laid down in the United Kingdom Defamation Act of 1952. The British Defamation Act was updated in 1996 and since 1952 many countries have passed their own defamation laws.

Although some defamation laws are clear in theory, you can only see how they work in practice by looking at court cases. In many developing countries, very few defamation cases have been taken to court so, for general guidance on how laws on defamation are applied, you may have to look at court decisions in other countries which have a similar legal system to your own. Although English decisions are not binding in independent countries, they may provide guidance for courts in your country on how to judge allegations of defamation.

One thing you should always remember - if there is any fear in your mind that you might be committing defamation, ask for professional legal advice before publishing. Most news organisations have lawyers they can call on for advice.

One problem with any laws on defamation is that they do not tell you what you may do; they lay down in broad terms what you may not do.

While the laws of defamation even in common law systems vary from country to country, a basic definition can be found in the British Defamation Act of 1952 which says defamation is:

The publication of any false imputation concerning a person, or a member of his family, whether living or dead, by which (a) the reputation of that person is likely to be injured or (b) he is likely to be injured in his profession or trade or (c) other persons are likely to be induced to shun, avoid, ridicule or despise him.

Publication of defamatory matter can be by (a) spoken words or audible sound or (b) words intended to be read by sight or touch or (c) signs, signals, gestures or visible representations, and must be done to a person other than the person defamed.

This is rather a complicated definition, so we shall split it into easy parts and speak about each part in more detail. There are three main parts:

First, there is "any false imputation ... by which (a) the reputation of that person is likely to be injured or (b) he is likely to be injured in his profession or trade or (c) other persons are likely to be induced to shun, avoid, ridicule or despise him."

In simple English, this means the words that were used, and their effect.

Second, there is "concerning a person, or a member of his family, whether living or dead."

In simple terms, this covers the identity of the person defamed.

Third, there is "Publication of defamatory matter can be by (a) spoken words or audible sound or (b) words intended to be read by sight or touch or (c) signs, signals, gestures or visible representations, and must be done to a person other than the person defamed."

This is usually shortened to publication, though it includes broadcasting.

If a person thinks that you have defamed them and takes you to court, they have to prove that all three of these things have happened.

Let us look at them one by one:

^^back to the top

The words

"Any false imputation ..."

An imputation means suggesting something bad or dishonest about someone. In most cases of defamation, this will be done using words although, as we shall see later, it is possible to defame someone by other methods, such as cartoons. For the moment, we will stick to words.

You can suggest something directly - by stating it as a fact - or indirectly, either by innuendo or by irony. Innuendo is a special meaning behind ordinary words. Words which seem innocent used in one way could have a special meaning in another.

For example, you might say a man "spent a year living in Bomana." To people outside Papua New Guinea, this might seem innocent. But people from Papua New Guinea know that the country's main prison is at Bomana, so the innuendo is that the man was a prisoner.

Irony is using words to imply the opposite of what they appear to say, as in the following example about Mr Hevi.

Here are two statements; one is a direct imputation, the other indirect. Either could be defamatory:

DIRECT:

Police Minister Mr Grissim Hevi has acted dishonestly while in office. |

INDIRECT:

The Police Ministry is an office for honest men. Mr Grissim Hevi is obviously in the wrong post.

|

It is also possible to impute something in a joking manner. Making a joke of an accusation does not prevent it being defamatory. This statement, if false, is just as defamatory as the two above:

If prizes were being given for honesty in office, Police Minister Mr Grissim Hevi would not be a main contender.

As mentioned earlier, in most English-based legal systems, the words are defamatory only if the imputation is false, but it is not the job of the injured person to prove that the statement is false. It is the job of the person who made the statement to prove that what was stated or implied was true.

It is not good enough for you as a journalist to say in court: "But I know that what I wrote about Mr Hevi is true." You have to prove it. Unless you can, the court assumes that Mr Hevi is innocent.

It is a foundation of English criminal law, that a person is innocent until proven guilty. In a defamation case, it is the journalist who has to prove the truth of the statement, and therefore the guilt of the plaintiff.

Although the imputation is normally done through the spoken or written word, you can also injure a person through a cartoon, a gesture or even a cleverly composed picture.

If your paper uses a cartoon depicting Mr Hevi secretly stuffing lots of money into his back pocket while looking guilty, the imputation is that he is a crook. That could be defamatory.

If your television newsreader finishes a statement from Mr Hevi denying any misconduct, then looks up to the ceiling in disbelief, that too could be defamatory, implying that the newsreader does not believe Mr Hevi's denials.

"(a) The reputation of that person is likely to be injured ..."

The law is there to protect a person's reputation in the community or society. A reputation is the general opinions of his personality and character shared by people in his community or society.

The law is not there to protect the reputation that he would like to have. The courts will judge what kind of reputation the plaintiff actually has, and whether it has been damaged. Although courts will not try to make a person seem better than he really is, it is possible to defame someone who already has a bad reputation.

For example, you may write a story about a man who has previously been convicted of assault. Your new story alleges that he has now stolen money from a church. If this new allegation is false (or you cannot prove it to be true) he could successfully sue for defamation, arguing that the little bit of good reputation he had left has now been damaged.

A false statement is not defamatory unless it discredits the person to whom it refers. To describe a man as "honest" may not be true, but it is difficult to imagine a court deciding that the word had damaged his reputation.

On a similar theme, the reputation which the law tries to defend has to be one which is held by "right-thinking members of society generally". It is not easy to define what a right-thinking member of society is. It is someone who usually obeys the rules and laws laid down by your society and who would agree with the majority of people about what is good and what is bad. Try to imagine an aunt or an uncle you admire; they are probably a "right-thinking member of society".

This definition is important because it is quite easy to say bad things about a person which might improve his reputation among certain people. If you called someone "unfeeling", it might actually improve his reputation in a criminal gang or an army unit, but it would hurt his reputation among right-thinking members of society.

The judge or jury will put themselves in the position of right-thinking members of society generally and to decide the effect the words would have on them.

You must, therefore, be extremely careful in your use of words. Ask yourself what they would mean to right-thinking members of society generally.

"(b) He is likely to be injured in his profession or trade ..."

The law not only tries to protect a person's good name or reputation, it also tries to protect their livelihood against damage by false claims. If, because of a false statement, a shopkeeper loses customers, an accountant loses clients or a policeman loses his job, they can sue for defamation.

In fact, the law does not say that the plaintiff must show actual proof of loss of earnings. It is enough that the false statement could have led to a fall in business or the plaintiff losing his job.

This does not mean that a journalist should avoid criticising the way in which people do their job; far from it. It is a journalist's duty to expose faults in any area. However, you must be careful exactly how you describe a person's professional faults.

It is always safest to stick to specific claims and not to generalise about a person's skills or professional conduct. In the following example, the first version is probably safe, the second is probably not:

RIGHT:

More than 30 sailors protested outside the Hunglo Shipping offices, claiming that the company's ships were overcrowded and unsafe. |

WRONG:

More than 30 protesting sailors claim that shipowners Ron and Wesley Hunglo are trying to kill them in overcrowded and unsafe ships. |

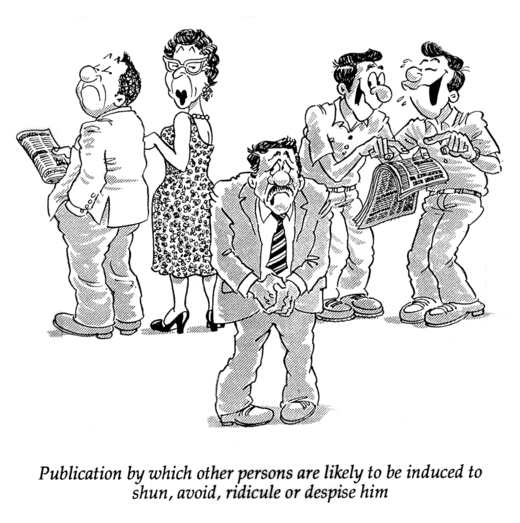

"(c) Other persons are likely to be induced to shun, avoid, ridicule or despise him ..."

Where part (a) above deals with a person's reputation, and part (b) deals with his ability to make a living, this section deals with the damage that can be done by changing people's personal behaviour towards the plaintiff. To shun means to keep away from someone; to ridicule means to make fun of someone.

Of course, if a person's reputation (either personal or professional) is damaged, then people will tend to avoid or shun them, either on a personal or a business level.

If a person’s reputation was injured by a false statement but he was unaware of it, you might argue that no damage had been done. However, if the plaintiff can prove that, because of what you have written about him, people show their low opinion by avoiding him, refusing to answer him or laughing at him, he will have a much stronger case in court.

In this case, the plaintiff only has to show that some people avoid, shun, ridicule or despise him because of what you wrote. He does not have to prove that everybody reacts in these ways.

In fact, the law does not even demand solid proof that people are avoiding or ridiculing him at all. All it usually demands is that, because of what you wrote, some people are likely to do it. Once again, the judge or jury will put themselves in the place of right-thinking members of society and decide whether they would be likely to avoid or shun the plaintiff.

For example, there is no social shame about the way people can catch leprosy (as there is in some countries to AIDS or venereal disease), but people will still shun lepers. If you falsely state that someone has leprosy, you may not damage his reputation, but you will almost certainly affect the way people behave towards him.

To make fun of a person can be as dangerous as to accuse him of some wrong-doing. Here there is particular danger for the cartoonist. The cartoonist who shows a public figure acting as a criminal is in danger, and so is the editor who publishes his work.

Although many public figures who are made fun of in cartoons choose to ignore them, there are times when they will feel angry enough to sue for defamation.

Words that change

As an added complication, you have to take into account changing standards. Words which might have been defamatory at one time may later become acceptable, and vice versa. Until the late Twentieth Century, the word "gay" usually meant bright and lively and was used as a compliment. Today it is more commonly understood to mean homosexual.

In some countries homosexuality is still illegal and therefore the word "gay" there has negative connotations. Even in countries where homosexuality is legal and widely accepted, if you falsely describe someone as being "gay" (i.e. a homosexual), they could get angry and sue for defamation. When a case goes to court, the judge or jury will not care whether the word once meant "bright". They will judge it on its current use and imputation.

In July 2008, a British businessman won a defamation case and £22,000 in damages at London's High Court after false claims about him being gay and a liar were posted on the Facebook social networking website.

^^back to the top

Identity

"A person ..."

The plaintiff must be able to prove that the words identify him as the person defamed. It is not necessary that he should have been specifically named. If he can show the court that a reasonable person would take the words to refer to him, he will probably have a good case.

It is wrong to think that you will be safe by making generalisations. Sometimes you increase the risk because, instead of aiming your words at one person, you are aiming them at a whole group of people.

For example, the statement: "I know of at least one senior member of cabinet who has made money by pushing contracts to his friends", is clearly defamatory of some cabinet member. If your allegations are true, the minister concerned may not try to sue you for defamation, but his cabinet colleagues could, arguing that people now believe that they are the guilty one.

Once you are sure of your facts, it is safer to be specific by naming the person. Once you lose accuracy and fairness in your story, you ruin any defence against a possible claim of defamation.

Although we usually think of "person" as an individual, it is possible to defame a group. Although the law varies from country to country, generally any group which has a legal identity - such as a company, a council or a trade union - can sue for defamation if you have harmed their business. (Under Australian media law, this is only true for non-profit organisations and companies employing 10 or more people.) Loose associations of people, such as people who meet regularly but casually, are not usually able to sue for defamation.

" ... or a member of his family whether living or dead ..."

It is usual to defame people by writing or broadcasting about things that they have allegedly said or done themselves. If, for example, you falsely accuse the Rev Milo Milord of having had sex with prostitutes, you have defamed him by injuring his reputation.

However, with occasional exceptions, common law usually holds that a dead person cannot take legal action, nor can living relatives on his behalf. If a person is dead, the law assumes that no further harm can be done to them. So you can say what you like about them without the need to prove your statements.

However, there is a small problem. Even though the Rev Milord is now dead, you may be able to harm the reputation of his widow, children or other living relatives by what you write about him. In this case, the living relatives can sue for defamation on the grounds that they themselves have been injured.

The Rev Milord's son, Marcus, himself a church minister, could sue for defamation on the grounds that his own reputation has been damaged by what you wrote about his dead father. People may stop coming to his church or may avoid him in the street.

Let us be clear, though: Marcus Milord cannot take action on his father's behalf to clear his father's name; Marcus would take action because he thinks what you said about his father causes him (Marcus) harm. He would do it to clear his own name.

^^back to the top

Publication

"Publication ... to a person other than the person defamed."

To be successful in a claim for defamation, the plaintiff must prove publication. Publication in legal terms means that the words or pictures must have been heard or seen by a third person. The first person is the one talking or writing (you), the second person is the person being talked or written about (the plaintiff), the third person is anyone else who may hear or read the offending matter.

There is no civil defamation if the words, however bad or untrue, are spoken or written only to the person about whom they are made.

The plaintiff must prove that the imputation (words, gestures or pictures) was communicated to at least one other person. As the law states: "Publication ... must be done to a person other than the person defamed."

In the case of newspapers, there is no difficulty in proving this; the contents of the paper are published to everyone who receives a copy. In the case of radio or television, a tape or transcript of the program is evidence of publication. Some broadcasters may try to deny that they ever said the words complained of, in the hope that the plaintiff will not have a transcript or tape of the program. Be warned: a judge will probably order the broadcaster to get a transcript or tape if the case ever comes to court.

"(a) By spoken words or audible sounds ..."

It is easy to see how words can be defamatory. But it is also possible to defame someone with a grunt or other noise. For example, a radio newsreader might read out a denial from someone, yet end it with a sound which suggests that he doesn't believe them:

Police Minister Mr Grissim Hevi today denied that he had been corrupt while in office ... uhm?

"(b) Words intended to be read by sight or touch ..."

This applies to print journalists and also to television when captions or parts of text are shown on the screen. It also applies to Braille, a language for blind people which they read by running their fingertips over raised symbols on a page.

"(c) Signs, signals, gestures or visible representations ..."

As we have already mentioned, it is possible to defame someone in a drawing or cartoon, or by pulling a face or making a gesture. If you point your finger at your head making a circular movement, in many societies this suggests that the person you are referring to is mad, that they have a "screw loose" in their brain. Such a gesture could be defamatory.

^^back to the top

A case to answer

The plaintiff has a good case if he can prove that:

- the words were defamatory

- they referred to him and

- they were published to a third party.

The plaintiff does not have to prove that he has suffered actual loss. It is enough to show that the words complained of are capable of causing him loss.

TO SUMMARISE:

Defamation is to spread bad reports about someone which could cause them harm

If the plaintiff can prove that the words had a defamatory meaning, identified him and were published, that is defamation.

This is the end of the first part of this two-part section on defamation. If you now want to read on, follow this link to the second section, Chapter 70: Defamation - what you can do.

^^back to the top