In this chapter, we discuss the reasons for fairness in reporting. We advise on ways of maintaining fairness throughout news gathering and news writing. We discuss the need for special care in writing comment columns, in campaigning journalism and in reporting elections and court cases. Finally, we show how corrections, clarifications and apologies can enhance fairness.

_______________________________________________________

There are three basic qualities which should guide the work of a good journalist - it must be fast, fair and accurate:

Speed comes from increasing knowledge, confidence and experience.

Accuracy comes from constant attention to details and from hard work in finding, checking and re-checking details.

Fairness is the hardest to define, but it has a lot to do with avoiding bias, treating people equally and allowing people to have equal chances to do things or express themselves.

What is fairness?

Even if you are not able to put it into words, you may have a natural understanding of fairness if you care about other people and are sensitive to their needs.

Fairness is made up of two parts: Objectivity and impartiality.

Objectivity means is not forcing your own personal opinions on the news you are reporting. The opposite of objectivity is subjectivity, which means putting your own feelings and personal opinions in the news you report.

Many people argue that objectivity is unachievable, that journalists are human beings and so will never manage to separate entirely their personal feelings from their professional practice. However, many people in their work and professions – such as judges, doctors and election officials - are expected to practise objectivity; so too should journalists.

And even when pure objectivity may not be achievable, it is no less important for that. Objectivity is like the harbour lights for a sailor or the landing lights for a pilot – to be aimed for and to guide us safely home.

If you strive to be objective in all your work, you will achieve it more often.

Impartiality means not taking sides on an issue where there is a dispute. Impartiality also includes presenting all sides of an argument fairly, what we call balance.

Even if you have strong feelings about an issue, you must not use the news to put over your own arguments; you must not try to give extra time or better coverage to people you agree with and less time or worse coverage to those you disagree with.

For the good journalist, objectivity and impartiality are two sides of the same coin. If you can be objective and control your personal feelings on an issue, you can also be even-handed in your treatment of all sides.

Although impartiality or bias can enter all areas of journalism, the greatest dangers lie in reporting politics, industrial disputes, religion, race and sport. Any area in which people have very strong feelings can lead to conflict and to bias in reporting the issue.

The same general principles which govern objectivity can also help you to be impartial. Forget your personal preferences while working on a story, stand back from it and try to look at the issues through the eyes of people both for and against. That may not change your personal opinion that something is wrong, but it will help you to be fair.

If you do believe very strongly in a particular cause, you must develop two personalities - the You-at-Home and the You-at-Work - and keep them separate. Many journalists in democratic countries support one political party or another. They may vote for a party or even be a member. But to keep a reputation as an unbiased journalist, they should not allow their party loyalty to influence their news judgment. The party supporter must be kept to the You-at-Home; the objective, impartial journalist is the You-at-Work.

Being objective is only part of the battle against bias. The other part involves recognising when one side in a dispute is applying unfair pressure to get their case in the news (or another side is not getting its fair share of coverage). This can be obvious and easy to correct, or more subtle and much harder to put right.

^^back to the top

Practising fairness

There are several ways you can allow personal bias to destroy objectivity and impartiality in the way you handle news. You should be aware of the dangers at each stage of the process of news production, from the first decision to cover a story through to its presentation on a page or in a bulletin.

Selection of news

Busy newsrooms are constantly having to make decisions about which stories to cover and which to ignore. The selection of stories can introduce a very basic bias if it is not done objectively. Simply because you disagree with a government, a group or an individual does not mean that you can suppress all stories which show the good side of them and cover only those which show them unfavourably. You should be even-handed. This is particularly important at such times as election campaigns.

Your decisions on which stories to cover should be made on the principles which govern what makes news. News should be new, unusual, interesting, significant and about people.

The exact balance of these criteria may vary depending on your audience. If you work for a scientific magazine, you may select different stories to a journalist who works in the newsroom of a pop music radio station. You must develop an accurate understanding of what is news to your audience, then be fair and consistent in the selection of every story.

Choice of sources

Even if you have to overcome a personal prejudice and decide to cover a story you find disagreeable, you must still take care that you are fair in your choice of sources of information. It is not fair to choose to interview an attractive personality for a cause you support but an unattractive or muddled person for a cause you oppose.

There is also the danger that, if you are asked to cover a story you dislike doing, you will fail to put enough energy into finding interviewees and arranging to talk to them. For example, someone you dislike may not want to talk to you. You must not say: "Oh well, let's forget him." You should try your hardest to get an interview or at least a comment.

If you want to be a good journalist, you should put your best effort into every story. That way you produce a good product and help objectivity.

"No comment"

In some cases people will be unwilling or unable to give an interview. Maybe they are just too busy, maybe they hate the sound of their own voice. Of course, you should try your very best to convince them they should do the interview, but if that fails you should not say: "Ah well, they had their chance and they missed it. I'll just give the other side."

You should still try for balance, even if it means finding someone else to speak for them or writing about their previous position on the issue. (Be careful, though, that your story makes clear that this is not a response to the present issue.)

Many journalists take the easy way out by writing: "Mr Rahman was not available for comment." They occasionally write: "Mr Rahman refused to comment", but this is unfair because it implies that everyone has a duty to speak to reporters. You can only "refuse" if someone is ordering you to do something. If you ask Mr Rahman for a comment and he will not give one, you should write: "Mr Rahman declined to comment." This tells your audience that you offered Mr Rahman the chance to comment, but he did not take it.

Always try to get some comment because using phrases like "declined to comment" shows that you are unable to present a fair and balanced report. If this happens too often, your reputation as a fair and honest reporter will suffer. But remember this: To maintain balance, you do not need to present both sides of an argument in one story, even though it is preferable. Balance will be achieved if you give an opposing view in the follow-up story.

Interviewing techniques

Do not abandon objectivity when you conduct the interview. It may be difficult to interview someone who stands for something you oppose or who has done something you dislike, but you must continue to be fair and accurate.

For example, if you are interviewing a drug addict or a thief, remember you are not there as a policeman or prosecutor. Do not demand answers in an aggressive tone. Keep your temper. The golden rule of all interviewing is to be polite but persistent.

Questions should be fair and you must take as much care when taking notes or recording as for any interview. If accusations have been made against the interviewee, do not make them sound like your accusations. Instead of saying: "You ran away from your responsibilities, didn't you?" you should say: "Critics say that you ran away from your responsibilities. Did you?" The outcome is the same, only the tone is fairer.

This advice applies particularly to broadcast journalists, some of whom like to ask aggressive questions for dramatic effect - the so-called tough interviewer. If that is your style, you must use it with everyone, not just the people you dislike.

Selecting material

Having conducted your interviews, you now have to put your material together into a story. Whether working for newspapers, magazines, radio or television, you have to select which facts and quotes to include and which to leave out. You will probably write your story in the usual inverted pyramid, with the most important things at the start.

Here again, you must be fair in choosing material. There are usually two sides to every argument, so do not be one-sided in choosing what facts to include or which words to quote. If your interviewee has said: "I support the present government, but with some serious reservations", it would be wrong to use only the quote: "I support the present government." Be fair and quote accurately, making sure that the meaning of each comment is put in context with what else is being said.

If the person you have interviewed stressed the importance of one particular aspect, do not omit it simply because you disagree with what was said. You should judge each comment independently under the criteria for what is news. That way you maintain objectivity.

Language

The language you use to write your story is very important. It is quite easy to change the whole of a sentence by adding one or two words loaded with a particular meaning. For example, your interviewee might have made some remarks quite forcefully. It would be wrong to describe them as "firm" simply because you liked him, or "harsh" because you did not.

Stick to facts. If he moved his finger as he made certain remarks, you can mention it but remember that there is a lot of difference between such words as "waved" (which some people do with their fingers naturally while speaking), "wagged" (which people usually do while telling someone off) and "jabbed" (which is used to make a forceful point or accusation). In fact, it is better to keep such descriptions out of news stories, although they can be used when writing features to show something about the person involved.

Any words you use instead of the verb "said" when attributing facts and opinions can add a bias to your reporting. Journalists often like to find alternatives for the word "said", because they think that repetition becomes boring. If you do use alternatives, you must recognise that some imply that you believe the person quoted while others imply that you do not believe them.

See the table below. The left column is words which imply disbelief, the right column words suggest belief, while the centre are reasonably neutral:

DISBELIEF:

claimed

alleged

inferred |

NEUTRAL:

said

spoke of

stated |

BELIEF:

announced that

pointed out

emphasised that |

Many journalists use a thesaurus to find alternative words to enliven their copy. A thesaurus should only be used if you have a very good understanding of the language. It is much better to use a dictionary to find the exact meaning of a word. If you use clear and simple language and leave out as many adjectives and adverbs as possible, you will limit the chance of bias entering into your copy.

Once again, if your interviewee accuses someone, you must make it clear that they are the interviewee's words, not your own. For example, if he says that the regime in Tilapia is brutal, attribute the remark to him, either in reported speech or in a quote. Do not allow it to be seen as your own comment. Remember, one man's regime is another man's government. One man's cabinet is another man's junta.

There are also good legal reasons for choosing your words carefully. In most countries you can be prosecuted for making false statements about someone which causes them harm. (For more details, see Chapter 69: Defamation - what you can't do.)

You should not blemish a person's name without a special reason, even though what you say is factually correct. There is no need to call a person who kills his daughter "a beast". If he has not been tried it is for the courts to decide his guilt or innocence. If he has been found guilty, your story will be stronger if you carefully and accurately record the facts without gory details and personal judgments. It will also keep your reputation as an objective journalist.

Compare the following and see which is both more objective and more powerful:

RIGHT:

At four o'clock on Christmas morning, Manuel Ortez walked quietly into his baby daughter's room and plunged a carving knife five times through the heart of the sleeping child. |

WRONG:

In the heavy dark of Christmas morning the fiendish beast Manuel Ortez slunk into his innocent daughter's room and, in a bloody frenzy, hacked the child to death with a gleaming knife. |

Predictions

There is danger of introducing bias in the tenses which you use when writing. When you describe what is happening or what has happened, it is natural to use present or past tenses. However, when you use the future tense to predict what you think may happen, remember that this is speculation. It may be well-informed and extremely accurate speculation, but it is not yet a fact.

It is safer to use words like "may" and "is expected to" when writing about events yet to come. If someone says they will do something, quote them as making the promise, do not let it seem that the prediction is yours. For example:

RIGHT:

The Finance Minister says he will reduce income tax before the end of the year. |

WRONG:

The Finance Minister will reduce income tax before the end of the year. |

Placing the story

If you are a sub-editor in a newsroom, you should be fair where you place a story in the paper or bulletin. Do not let personal feelings interfere with your news judgment. Just because you are strongly opposed to whale hunting, you cannot choose to lead with that and put the story about the Prime Minister's assassination further down if they are both new. There is no excuse for hiding a story down the page or bulletin simply because you do not like what is said.

Your readers or listeners may disagree with you over the order in which you rank stories because they also have special likes and dislikes. But if you are fair and follow the guidelines of news value, you will be able to defend your news judgment against all sides.

^^back to the top

Comment columns

There are opportunities in the media for journalists to give their personal opinions - in writing reviews and in the commentary columns of newspapers and magazines. Journalists usually write under their own name or use a pseudonym (a made-up name). A special column called the editorial or leader column is where the paper gives its own opinion on specific topics such as a new foreign policy or a harsh prison sentence.

Any commentary column should clearly show that the statements are the personal opinions of the columnist or the opinion of the newspaper itself. This is normally shown by placing the column in a regular slot on a specific page. The title of the column or the inclusion of the author's by-line usually indicate that the column is that person's own comments. Some newspapers even use a small block saying "Comment" at the top of such columns.

Unfortunately, many journalists allow their own comments to spill over into genuine news reports. Well-educated readers can tell where fact ends and personal opinion begins, but less educated readers can be confused.

For a more detailed discussion, see Chapter 50: Features and Chapter 52: Reviewing.

Commentary on radio or television

There is really no place in radio or television for newspaper-style commentary columns (for reasons which we discussed in Chapter 56: Facts and opinion). If you think it will help your listeners to understand an issue by giving them some expert comments, it is better to bring in experts rather than do it yourself. This is best done in an interview in a news or current affairs program. If a politician wants to express an opinion on an issue which the newsroom does not regard as newsworthy, they should apply to buy air time for a party political broadcast, if these are allowed.

Occasionally an editor will ask people like foreign correspondents or specialist reporters to give an analysis of an event. Such segments should be kept factual and free of personal bias.

Radio and television stations may also allow their journalists to express personal opinions in reviews, perhaps reviewing a film on an arts program or judging a recipe on a food program. Such reviews should be kept separate from news bulletins and should be clearly identified as the personal views of the journalist concerned.

^^back to the top

Campaigning journalism

Sometimes journalists come across things which affect them emotionally. These can be injustices, cases of cruelty or simply people who need the help of the media. In such circumstances journalists take one side of an issue and fight for that side. For example, journalists have campaigned against bad prison conditions, against political oppression or against street crime. Clearly they are not being totally objective, and in such cases the reader or listener understands why.

However, campaigning for a cause should not stop you attempting to be as objective as possible in your treatment of a story. You should still prefer facts to opinions and give people a chance to answer any allegations made against them. If the situation is really as bad as you believe it is, simply giving people the facts will be enough to convince them. Let your audience judge the rights and wrongs of the issue.

The purpose of campaigning journalism is to make other people feel deeply about something, just as you do. The best way to do this is to ask yourself what made you feel the way you do: what did you see or hear which convinced you? Whatever it was, that is what you should present to your readers or listeners, so that they might have the opportunity to feel about the issue, just as you do. If you want somebody to know what it is like to have a pin stuck in them it is a waste of time standing next to them crying in pain. It is much more effective to stick a pin in them! Similarly, saying how deeply you feel about injustice will not convince your listeners; put the injustice in front of them to see for themselves.

Campaigns often take a long time and journalists can become so involved in them that they lose sight of the original issue. It is a good idea occasionally to stand back from the issue and assess objectively. Ask yourself: "Am I still being fair and accurate? Have I exaggerated my case?"

The golden rule about objectivity is to be honest about yourself. If you recognise personal prejudice in your work, fight against it. At the end of the day, your reputation as a journalist who can be trusted is at stake.

^^back to the top

Contacts

Journalists rely on contacts to tell them what is happening or give them hints on stories which might be worth covering. Contacts can range from an official within the government to the boy who keeps his eyes open for stories while selling newspapers.

Some contacts will tell you things simply because they like you or they like the idea of being involved in the media in a small way. They are not part of the story and have no particular interest in giving you one side against another.

Others, however, will tell you things because they want the news covered in a certain way. These people can be politicians who expose an opponent's wrong-doing to score political points; company public relations officers who want to sell a particular product; activists who want to highlight what they see as an injustice; a criminal who wants to get even with a corrupt policeman by "telling all". The list is endless. They all have one thing in common - they are not interested in balance, they will not help you to give the other side of the story. You can use such contacts to give you story ideas, but must go to other sources as well for balance.

Public relations

It is easy to be drawn into taking the side of contacts, for all sorts of reasons. Businesses, governments, politicians and police forces in particular have recognised the value of employing special people to present their case to the media and the public. Whether they are called public relations executives or press officers, they still owe loyalty to the person who pays them. They are not there to help the media, they are there to protect and promote their employers.

The clever public relations officer or PR will be very pleasant to deal with. He or she will always try to be available to journalists, even at home. They will call you by your first name and share jokes with you. They will arrange interviews for you and issue press releases to keep you informed. They will, in effect, do everything they possibly can to make your job easier and save you digging for a story. They know that journalists who dig often find more than they were originally looking for.

They also recognise a basic fact of human nature, that if journalists can get news more easily from one side than the other they will favour that side over the other, either consciously or subconsciously. It is difficult for young journalists to have a very friendly chat with a helpful PR then write something critical about his company or organisation. How much easier it is to take their side against the opponent who angrily accuses you of trying to stir up trouble then slams the telephone down!

As well as finding the good PR more pleasant to deal with, journalists may also find them better informed and better communicators. Many companies, political parties or pressure groups now either employ professional journalists as public relations officers or send their PRs on special courses to learn how to handle the media.

So beware of the temptations offered by public relations officers. It is much easier today for a busy reporter to ask the PR manager of a shipping line to get a comment from his chairman than it is to go out and track down the opposing union official who also works full time "down on the dockside somewhere". To be a good journalist you must accept that some tasks are easy, some are difficult. Do not allocate the same amount of time to getting each side of the story - aim for the same level of achievement.

Conflicting news sources

Whenever you are getting news from a number of independent sources, whether they are wire services, contacts or witnesses, you may find conflicting information. In some cases these may be small variations, in others major differences.

For example, you may have been given two different days when strike action is due to start. By checking back, double checking and cross checking sources, it may be possible to find where the difference lies and deal with it easily. Often a phone call is all that is needed.

In other cases, where your access to information is limited, you may never be able to find out exactly who is correct. In such cases you should attribute the facts in doubt to the individuals, groups, companies, organisations or governments which gave them. For example, if one army claims to have fired three missiles and their enemy says they only fired two, quote both sides and let the reader or listener judge from experience who to believe. If you are still unhappy about that solution in really controversial areas, leave out the details in question.

Sometimes you may receive conflicting details from two usually-reliable news agencies. For example, Reuters may say that 1,000 people have been killed while Associated Press says 2,000. If you cannot see an obvious reason for the different figures (such as the AP story being more up-to-date than Reuters), contact the agencies themselves, perhaps by telex. If you cannot determine which is correct, you may have to quote both of them - as long as you are sure that this will not confuse your audience. You must, of course, clarify the situation as soon as possible. The alternative is to wait until the situation is clearer before running the story.

Whenever there is conflict between two reports from the same agency, look for reasons why (such as one report being more up-to-date or from a bureau nearer to the event). Again, if you cannot find an obvious reason, contact the nearest branch of the agency for an explanation.

^^back to the top

Favours

As a journalist, you must never accept a favour or a gift if you suspect that it is being used as a bribe. They can quite easily affect your credibility as a journalist.

If you accept any gift on the understanding that you will write favourably about the donor - whether they offer a carton of beer, a car or a trip abroad - you have said that there is a price on your honesty as a journalist. You can be bought. You are no different from the corrupt policeman who publicly defends the law but privately commits crimes.

Even the smallest gift or favour destroys your credibility as a fair journalist. By breaking down your protection of honesty, it also makes it easier to accept the next bribe, then the next.

Even if the gift does not make you act any differently, you might find it difficult to convince other people of this. The donor might also try to blackmail you over the issue to get your support.

If someone offers you anything free, such as a sample of their product or a free holiday to try their hotel or airline, you should tell the news editor or director of news immediately. They will then decide whether or not you can accept it. It might be possible to accept it, but only on condition that everyone involved knows that it will not influence your judgment. If the car you test drive is bad value, you will say so. If the airline is unpunctual, dirty and overcrowded, you will write that too. Very few public relations officers would offer you a direct bribe, but they might wrap it up in an innocent-looking offer. (See Chapter 58: Pressures on journalists.)

^^back to the top

Elections

You must be especially careful about being unbiased during elections. What you write could alter the outcome.

It is the journalist's duty in a democratic society to keep the people well informed of the choices available to them at election time. You should report who the candidates are, what their policies are and what are the main issues of the campaign. You should also tell people what is happening in the campaign generally, who is saying what, where and to whom. Only if the electors are well informed can they make wise decisions about voting.

Journalists usually have plenty of material at election times. The politicians and their parties make sure that the media are told about what they are doing and saying. Many politicians and parties now employ press officers to feed the media information which shows the candidate or party in a good light.

Poorer politicians and smaller parties may not be able to employ specialists and have to do such work themselves. An independent media should make sure that no-one gets an unfair advantage because they have more money to spend on campaigning.

Often the best way of ensuring fairness and balance is to set guidelines at the start of the election on how the candidates and parties will be treated.

Some newspapers and broadcasting stations try to give each a fair share of publicity by counting the number of column centimetres or amount of air time each one gets. This would only include stories which can be seen as campaigning. For example, you could count stories about campaign trips, appearances, speeches, policy statements, predictions about polling and attacks on opponents. You would not count hard news stories about the candidates, such as an appearance in court on a driving charge. Because such hard news stories are usually bad for the person concerned, one cannot argue that they are helping his or her campaign.

This approach has a number of variations, such as allowing space in proportion to the size of parties or number of candidates they are fielding. Thus in a situation where there are two major parties and one minor party and a few independents, the paper or station may decide to allow the major parties 35 percent of the election coverage each, the minor party would get 20 percent, and the independents would get 10 percent divided equally between them.

In practice, this should not mean censoring news, simply keeping a daily or weekly check on how much the parties and candidates get and adjusting them to get a balance over a period of time.

Your country may have laws governing how much time or space you must give each candidate or party to maintain balance. In many countries, broadcasting laws state that balance must be maintained and records kept throughout the campaign period. You must check what the law says in your country.

^^back to the top

Reporting court cases

It is especially important to be fair when reporting court cases. The whole point of a court case is for the law to decide guilt or innocence. It is not your job to take sides and either condemn or clear someone in print or over the airwaves.

Not only is it very unfair and undermines the impartiality of the legal system, it is often against the law. If a court thinks that you are trying to do its work for it, you may be prosecuted for contempt.

In some countries, such as the United States, journalists can make all kinds of comments about current legal proceedings. This is because the American Constitution has to balance the individual's right to a fair trial against the First Amendment protecting free speech. In countries which have based their laws on the English legal system, the balance is in favour of a fair trial; free speech has to be limited to protect the individual's right to a fair trial. The judge or jury must not be influenced by what they read or hear on the news (see Chapter 68: Contempt).

All reports of court cases should be fair and accurate giving time and space to both prosecution and defence. Any comments on the case must wait until the case is over.

(For a more detailed discussion on balance in reporting court cases, see Chapter 64: The rules of court reporting.)

^^back to the top

Public displays of support

It is often difficult for journalists not to get involved in some issues. Your everyday work brings you into contact with injustices and cruelties of all sorts. Some journalists feel the need to do something, not only to write about it. There are also others who become journalists because they support a particular cause. Although they may try hard to be objective and impartial at work, they may continue to be a member of a political party, organisation or pressure group in their free time.

If you take sides on any issue, as a journalist it is not wise to show the fact. Opponents may use it as a weapon to attack your reporting, even though you feel that you are being entirely objective.

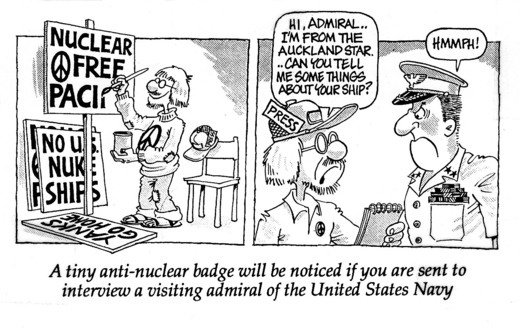

So avoid wearing T-shirts or badges which show your support for a particular group. Certainly never wear them at work or when conducting an interview. Even the smallest badge or sticker can lead people to think that you are biased. For example, a tiny anti-nuclear badge will be noticed if you are sent to interview a visiting admiral of the United States Navy.

As long as you are a reporter, you should avoid taking a leading role in public demonstrations, speeches or rallies. You should also avoid taking a public role in any controversial organisation. For example, being a Scout or Guide leader is acceptable, but giving a speech supporting a political candidate is dangerous.

Once you are publicly seen to be taking sides, you will never convince people again that you are impartial, even though professionally you may be.

^^back to the top

Corrections and apologies

Nobody likes publicly admitting they have made a mistake, but there are several good reasons why journalists publish corrections, with or without an apology. These include:

- Truth and accuracy are cornerstones of professional journalism, so publishing or broadcasting something untruthful is a major failing; the sooner mistruths can be rectified the better.

- A correction sets the record straight. Although a correction will not appear at the same time or in the same place as the original, it will not leave an error uncorrected for future readers or listeners. In online stories, a correction can accompany and counteract the original error.

- False information will not stay hidden anyway. More than four centuries ago, William Shakespeare reminded us “the truth will out”, meaning that however much one might try to hide mistruths, they will eventually be revealed. If known errors are not corrected by you, they will be revealed by someone else, undermining your reputation.

- Corrections and apologies strengthen your relationship with your audience. Far from undermining their confidence, issuing a correction and apology says to them that you respect them and that you trust them to forgive you.

- Making a correction can help to disprove accusations that journalists only spread false or fake news. Because everyone makes mistakes, an individual or media organisation that never admits to making an error is obviously lying.

- Corrections are fair to the people about whom the mistake was written. If information about a story source, commentator or interviewee is wrong, it can make them appear untrustworthy or foolish, so a correction can restore the reputation you may have damaged. Many people who come into contact with journalists feel we “never get things right”, so to remedy this, when we make mistakes we must demonstrate we don’t do it on purpose and we can be trusted to correct errors.

- In cases such as defamation where an error has legal ramifications, an attempt to correct an error will be recognised in court as an effort to minimise harm and so may reduce any penalties.

What are corrections, clarifications and apologies?

A correction is simply admitting that wrong information was provided to your audience and should be replaced by the new information. An apology takes this one step further, offering your regrets that the correct information might have done harm to someone.

A correction might also offer an explanation as to why the error was made, perhaps names were transposed or words were missing from the published story.

A clarification is a kind of correction – without admitting there was anything wrong with the original article or item. A clarification is usually phrased as presenting less ambiguous or new information not contained in the original story. Clarifications are often made in response to complaints by people identified in the original piece in circumstances where the journalist does not feel the need to admit to a mistake, just to clarify something. For example, if someone complains that a story implied they had done something wrong, the clarification might state: “The Herald did not intend to suggest Mr So Andso was in any way responsible for the accident.”

When and where to make a correction and/or apology

Ideally, a correction should be published as soon as you know a story was misleading or facts were wrong. This will minimise the chance of damage. In live broadcasting that can range from correcting an inaccuracy as you are speaking (for example “I’m sorry, that should be Lisbon”) to correcting it at the end of the bulletin. If you play the wrong report or interview, you should apologise to your listeners at the time, rather than let it run without mentioning it. That is disrespectful to the listeners.

If you cannot correct an error straight away – perhaps because you don’t know the correct facts – then you need to plan how you can correct it at the next opportunity – perhaps the next bulletin or during the same bulletin the following day. It is important you consider whether the same people might be listening or viewing as heard the original error.

For print media, it is generally expected that the correction will be made in the next edition or – if you need time to consult your supervisors or lawyers – in the next appropriate issue. It is also ethical to give the correction similar prominence to the original story, perhaps on the same page in the relevant edition or attached to a follow-up story. It is not ethical to try to hide the correction. This will not satisfy either the conditions listed above or the readers affected by the original error. [See the Case Study below.] In many countries, Press Councils or Media Authorities, when adjudicating a complaint about an error, might insist the correction be placed in the same place in the paper, magazine or program as the original article.

For online media, the correction can be made to the posted story but there should also be a reference to the correction in a footnote (or Editor’s note) at the end of the revised story. For example, “Correction: Comments attributed to John Smith in an earlier version of this story were, in fact, made by Joanna Smith.”

In social media, the correction can be made in a re-edited post where possible (with reference to the original mistake, as above) or in a follow-up post or Tweet, again making reference to the earlier post. The important thing is that your readers are not left with the wrong information. For more on publishing re-edited Tweets, see “unpublishing” below.

How to frame a correction and/or apology

Corrections and apologies should not make matters worse. If you make a correction or apology, it must be genuine and clearly expressed. There is no point in correcting an error that leaves your audience more baffled or in apologising reluctantly in such a way that the people to whom it is directed do not recognise or accept it.

Corrections should be clearly headed as such, not as an "Update" or "Editorial Comment". If it is a correction or an apology, call it that. Both should be written with care and be especially accurate; no-one wants to issue a "correction to a correction".

You can use the same tone of language as the original story. If it was a serious article, the tone of the correction should be serious. You can use a more light-hearted tone when correcting a humerous article.

If you need to use the original article again after publishing a correction to it, make sure that original article is properly corrected. See unpublishing below.

If you work as part of a team, seek guidance and advice from your colleagues. If you work in an organisation with different levels of responsibility, you should seek approval from your supervisor before drafting and publication. If the matter has any legal implications – and many seemingly ordinary mistakes can eventually lead to legal action – you or your supervisor should seek legal advice, perhaps from the company lawyer, about making corrections or apologies.

Fake apologies

In particular, an apology should address the issue for which you are apologising, not other issues or even the reaction people might have had to the original error. There is no excuse for publishing fake and half-hearted apologies, such as “we are sorry some people feel offended”. You will only make matters worse by blaming people for feeling offended. Be honest and clear: “We apologise for any offense the imputation may have given readers and those people concerned”.

You can say you never intended offending anyone, but you should still admit when something you wrote or said in error did cause offence.

A case study

In October 2020, an Australian court had to step in to force a broadcaster to publish a genuine clarification in a more prominent place on its website after the network tried to hide it in a page rarely visited. The case started when Channel 10 reached an out-of-court settlement with a man who said they had implied he killed his partner. The network agreed to publish a clarification, but then inserted it on their Terms and Conditions page, which Federal Court Justice Anna Katzmann said was “a place where it was highly unlikely to come to anyone’s attention". She called 10’s action “an act of bad faith” and ordered they republish the clarification on a page of the 10play website relating to the program where the original implication was broadcast.

You can read a report of the case here.

Complaints and corrections procedures

Many major news organisations in free press democracies have clear in-house policies on corrections and apologies, with senior staff designated to deal with them. The Washington Post, for example, publishes details of its system online, for transparency. The New York Times not only makes information available on complaints and corrections but it has a special page online where it publishes all stories that have been corrected. Although the British Guardian newspaper also has a special online page for complaints and corrections, they are partly hidden behind a requirement to “register to keep reading”, though registration is free.

Australian media are generally less helpful and less proactive towards receiving audience complaints and publicising corrections. Although the Australian Broadcasting Corporation has complaints-handling procedures, the ABC’s online “Corrections and clarifications” page contains only brief information about the specific error corrected, unlike papers like the New York Times which re-publishes corrected stories in their entirety. As of May 2022, News Corp in Australia made its readers and other stakeholders fill in forms on their Contacts page or search pages such as Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for information on how to complain or correct published stories in News Corp media such as news.com, the Daily Telegraph or The Australian newspaper.

Unpublishing online*

Unpublishing online, by removing an already published article, blog, social media post or other material, may seem a simple, straightforward way of dealing with matter which contains errors or is the subject of a complaint. In theory, it simply disappears.

However, there are several issues associated with online unpublishing that can make it controversial or even wrong.

Although the practice of unpublishing has been around as long as internet journalism, the issue has become increasingly relevant as traditional publishers move online and as people realise that what they publish (or post) can have long-lasting negative effects on their own futures. Numerous cases have emerged where people with valuable public profiles – such as actors, artists and politicians – are called to answer for things they said or posts they made to social media years before.

Typical of such a situation was that of Australian electoral candidate Katherine Deves who found herself selected to run for the conservative Liberal Party in a Sydney seat that had just voted out their previous MP - a hard-line conservative former Prime Minister - for a more progressive independent candidate. Realising she would be out-of-line with this trend in the constituency, Deves deleted hundreds of social media posts she had made over the years attacking transgender young people. Unhappily for her, copies of these posts in archives and on other people’s threads emerged during the campaign and Deves lost, despite the personal backing of then Liberal Prime Minster Scott Morrison. Unpublishing her posts was Deves’ attempt to bury important information about her politics and character, and the result showed how such actions can be fraught with perils.

Reasons not to remove online material

Of course, sometimes journalists have no choice but to unpublish material, especially if it is legally unsafe or entirely false. But it should never be done without considerable thought and expert advice, for several reasons, including:

- In lengthy or complex articles or series, the removal of segments or instalments can leave fatal gaps in logic or arguments that online readers require to properly understand the issues.

- Removing elements of controversial issues can destroy the balance of an article or a sequence of posts.

- Unpublishing can cause problems with archiving, as some versions of an article may disappear while copies remain elsewhere.

- On social media threads removing a post can make other parts of the thread incomplete or incomprehensible. Missing posts can also make people who post after it appear ridiculous.

- Removing an article or post can leave an obvious gap, leading readers to wonder what you have to hide.

- Removing an online article or post does not mean it was never published. If people had already read it, legally it was published. While removing material for legal reasons may be necessary, you might still be exposed to legal action.

- In most cases, if an article or post contains errors, a better option might be to correct it, as discussed above.

Many news organisations have developed Codes to guide journalists about unpublishing online material. These are well worth every journalist reading to understand the ethical issues and practical processes.

The ABC in Australia has detailed guidance for its staff on removing online content. It includes advice such as:

- “It is always preferable to correct, clarify or update content rather than removing it.”

- “When content is temporarily removed, the ABC aims to republish it as soon as possible.”

- “Any decision to remove content must be upwardly referred.”

- “Receipt of a complaint or legal threat is not, of itself, sufficient grounds for removing content. We do not remove content pending the investigation of complaints, other than in exceptional circumstances.”

- “[In cases of changing community standards], contextualising the content, and warning audiences about its potential offensiveness, is generally preferable to removing it.”

- “When an Indigenous person dies, it may be appropriate to temporarily remove some ABC online content featuring the person’s name, image or voice.”

- “We may be required by law to remove some stories that refer to historical, minor convictions. […] Any request to remove or amend a story because a conviction may be spent must be upwardly referred.”

- “At various times courts will make orders that require the media to remove particular content. The ABC will always abide by such orders, however, consult ABC Legal before removing content to ensure strict compliance with the terms of the order.”

- “Demands to remove content [because it is allegedly defamatory] should be referred to ABC Legal before any action is taken.”

- “An invasion of privacy may be a legitimate reason to remove or anonymise content under ABC Editorial Policies. Upwardly refer ….”

Footnote: * Unpublishing here is the verb, meaning to remove something already published online. Unpublished as an adjective refers to material that exists in draft form, before publication. For example, a writer may produce an unpublished manuscript that has yet to find a publisher.

Fix it later

Finally, a word about the temptation to “fix it later”, a trend which has developed in online media, where deadlines are more flexible than they were in legacy print media and broadcasting. In pre-internet publishing, once the newspaper or magazine had been printed or a tv or radio bulletin had gone to air, there was no chance to fix any errors. The only option was to correct any mistakes later.

With online publishing, where there are often no set deadlines, the drive to post the story online straight away can lead to journalists publishing or posting too soon, before the story is ready and before it has been thoroughly checked and any corrections or omissions have been addressed.

But remember, the same flexibility of deadlines means you can afford to work on the story a bit longer, checking that you have everything correct before you press the Publish button. It is much more efficient to spend extra time avoiding errors than being forced to correct or re-publish later, perhaps with added burdens from complainants and lawyers.

And keep in mind that while corrections may sometimes be necessary, mistakes are never good.

TO SUMMARISE:

Reporting should be objective and impartial

Be fair in your:

- selection of news

- choice of sources and interviewing technique

- news writing

- use of the story

Avoid open displays of support for one side in a conflict

Corrections, clarifications and apologies must be published where necessary and in a suitable form.

Unpublishing online is more than simply pressing Delete, and it must be done with due thought.

^^back to the top

>>go to next chapter